News - GLOBE Observer

Two “Edgy” Mosquito Stories

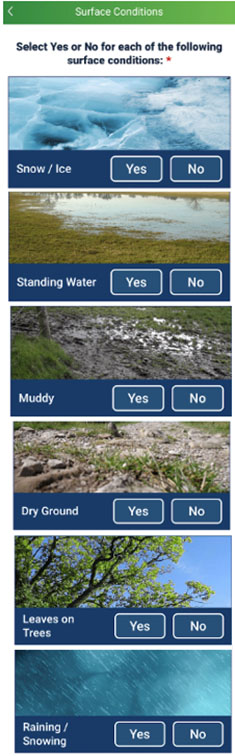

The first question in the GLOBE Observer app’s Land Cover tool asks you to identify the surrounding surface conditions. “Is the surface wet or dry?” “Is there snow or ice?” These questions help us understand what you are seeing and what is recorded by your phone and by satellites in space. Your answers provide valuable information about air temperature, precipitation, cloud cover, etc., and they document the physical environment exactly where and when you are recording your observation.

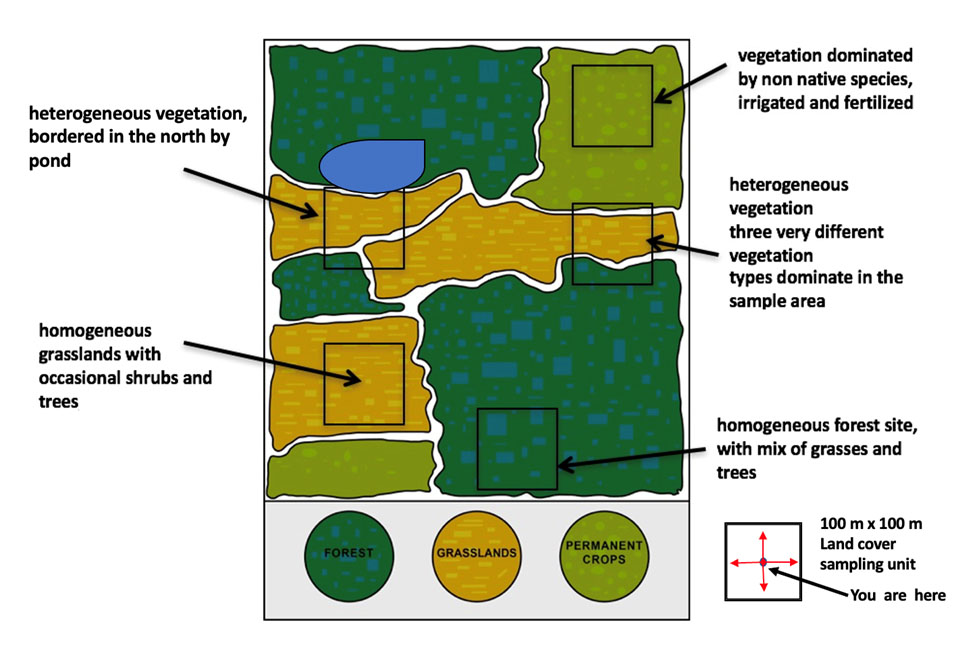

The second question in the Land Cover tool asks you to take a photo in each of the four cardinal directions: north, south, east, and west, as well as up and down. Why do we ask for more than one photo at each location? This is because it allows us to determine whether the observation is being made within a homogeneous or heterogeneous landscape. If the 50-meter viewshed captured by your camera shows similar vegetation types and land cover features in all four directions, we describe this as a homogeneous landscape. On the other hand, if the viewshed shows distinctive features in one or more directions, the landscape is heterogeneous.

Heterogeneous land cover includes “edges,” or transitional zones, where organisms that typically remain isolated in independent habitats can come together and interact. These zones, called “ecotones,” are known for their species diversity and a wide range of microhabitats. Scientists are especially interested in documenting mosquitoes found in these edge zones because these are places where mosquitoes encounter new hosts and new pathogens, creating new opportunities for disease outbreaks.

Mosquitoes thrive in environments that provide the following conditions: favorable temperatures, standing water and vegetation with food and shelter for adult mosquitoes. Most importantly, female mosquitoes need access to organisms to bite, so they can obtain the blood needed to produce their eggs. Think about these factors when reading the following stories that demonstrate how physical factors are responsible for why mosquito populations are unevenly distributed on the landscape.

Story 1: Environmental factors are responsible for changes in mosquito population distributions.

Geologist Dr. Doug Schnurrenberger was part of an interdisciplinary archaeological team excavating the Bluefish Caves in the Northern Yukon Territory, with a crew assembled by the National Museum of Canada. The Bluefish Caves contain some of North America's oldest evidence of human habitation, dating back to around 24,000 years ago! The site was remote and accessible only by helicopter, and the research camp had no water or electricity. A hole dug into the permafrost supplied refrigeration for food.

Archaeology is hot and dirty work, and after about three weeks of working on the open, windswept ridge, a creek about 250 meters down in an adjacent valley looked inviting. Dr. Schnurrenberger decided to hike down to the creek. He took a pleasant swim, washing off three weeks of dirt and sweat, swatting occasionally at the mosquitoes living near the water.

When it was time to walk back, it seemed a lot steeper going up than it was coming down. As he hiked back to the site, Dr. Schnurrenberger was breathing hard, expiring lots of carbon dioxide, a strong attractant for female mosquitoes looking for a blood meal. He quickly found himself surrounded by a cloud of mosquitoes. Dr. Schnurrenberger sped up to outrun them, but it only caused his breathing to get harder and harder, and more mosquitoes swarmed around him!

He finally got to the top, and the rest of the team was sitting around a fire. They saw Dr. Schnurrenberger emerge through the trees, surrounded by a visible grey cloud of mosquitoes. "Watch out!" they cried, scrambling for cover. Luckily, the breeze picked up and blew the mosquitoes away before reaching the team.

Story 2: Why do mosquitoes stay under the forest cover during the day? Why are they laying their eggs in the forest?

In 2017, the GLOBE Observer team piloted The GLOBE Program’s GLOBE Observer app’s Mosquito Habitat Mapper tool in Brazil, working with GLOBE teachers and students across the country. The team had looked around the school grounds for mosquito larvae specimens to examine during a lab workshop, but there were no standing water sources and no adult mosquitoes to be found. One teacher suggested trying to search the edge of the fields, where an adjacent forest plot was located.

Entering the shade of the forest's edge, the team was relieved to experience a decrease in temperature. The comfort was short-lived, as they were bombarded by a multitude of biting mosquitoes. But, why were there so many mosquitoes at the edge of this forest?

Human disturbance often creates new mosquito habitats, and it was evident that the bamboo stands within the forest had been repeatedly harvested by the local community. This left the hollow bamboo stem to be filled with rainwater. The cut bamboo stems had become perfect natural containers and protected breeding sites for mosquitoes. It was evident that human land cover modification in the forest had created an enormous mosquito nursery!

So now you know the answers to the Story Number 2’s questions: The forest provides shelter from wind and direct sunlight for adult mosquitoes, and protects puddles of standing water from rapid evaporation, making forest cover an excellent place for adult mosquitoes to find suitable oviposition (egg laying) sites as documented here. Human modification of the landscape (forest cutting, urbanization, irrigation, etc.) typically results in increased availability of mosquito breeding sites and increases in mosquito populations.

You too can use the GLOBE Observer app to document mosquito habitats you find in YOUR local community. Pay attention to the “edges” you see in the landscape. A great place to look for mosquito larvae is at the water’s edge (just like where Dr. Schnurrenberger first encountered them) or in a forest (as detailed in story number 2).

Plus, you can share your observations during the “Where is the Water? A GLOBE Observer Data Challenge.” The challenge begins May 1, 2023. More details will be posted to the challenge information page as the date draws nearer.

In advance of the data challenge, you can join the author Dr. Russanne “Rusty” Low and share your experiences and "edgy” mosquito stories at GO Connect (a virtual conversation space) on Thursday, April 6 at 12 p.m. and 8 p.m. ET. Learn more about GO Connect and register.

About the Author:

Dr. Rusty Low is a senior Earth scientist for the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies, Arlington, VA, and the science lead for GLOBE Observer Mosquito Habitat Mapper.

Comments

View more GLOBE Observer news here.