News - GLOBE Observer

Blogging from the Field: Mosquito Habitat Hunting in the Sky Islands, Southern AZ

Rusty:

When we told our friends we were going to Tucson, Arizona to look for a specific mosquito, they didn’t believe us. How could mosquitoes thrive in a hot, dry desert? Well, they can’t, but not all of southeastern Arizona is desert.. Our expedition took us instead to an ecologically unique and biologically diverse region called the Sky Islands.

The Sky Islands are isolated mountain ranges that loosely connect the Rocky Mountains in southeastern Arizona and the Sierra Madre in Northern Mexico, separated from each other by the Sonoran Desert below. Some of the mountain’s summits are more than 6,000 ft above the desert floor (more than a mile high), and the cooler and wetter conditions at these upper elevations support highly diverse and unique ecosystems. The region is called the Sky Islands because these mountain ecosystems are isolated from each other by the harsh dryness and extreme heat of the desert surrounding them at lower elevations.

We were on the hunt for a mosquito assassin species called Toxorhynchites moctezuma, let’s call them “Tox.” Members of this genus of exclusively predatory larvae evolved an adaptation to avoid becoming food for fish and other permanent water predators, by preferentially laying eggs in tree holes -- often tree knots that have rotted away, leaving a depression where water can collect. Here, a variety of tiny aquatic organisms, including some species of mosquito larvae, thrive. The ever-hungry Tox larvae will feed on any other aquatic invertebrate creature that is small enough to consume, including other mosquito larvae. In fact, Tox larvae consume so much protein as “mosquito assassins” that as adults, females do not need to bite and obtain a blood meal to make their eggs. Tox are very special mosquitoes that don’t bite humans!

Anita:

I’m especially interested in Tox mosquitoes because we are employing the species Toxorhynchites rutilus as part of our integrated pest management strategy in Harris County, Precinct 4, Texas. Toxorhynchites rutilus is also known as the elephant mosquito because of its long, trunk-like proboscis specifically adapted to reach down into flowers to obtain nectar, but we prefer the name “mosquito assassin” as it describes its predatory nature. I’d like to add Toxorhynchites moctezuma to our line up as biocontrol agents since this species isn’t quite as dependent on high humidity as our native Texan Toxorhynchites rutilus, which goes into a state of quiescence during the summer heat. I’m hoping to find enough Toxorhynchites moctezuma larvae during the expedition to start a new colony back at my lab.

Even though we were in the Sonoran Desert, it was cool and rainy in the Sky Islands because we were there in the middle of the annual monsoons. Our search took us to riparian oak woodlands and to dry river washes lined by tall trees. Sycamores and oaks in this biome provide plenty of opportunities to investigate tree holes to determine if they are currently serving as mosquito larval habitats.

This requires a bit of detective and agility work. Sometimes the hole is very small but opens to a large cavity inside where small aquatic organisms, like mosquito larvae can thrive; sometimes the hole is just out of reach.

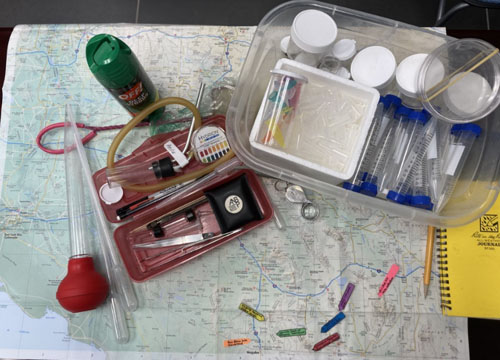

Once water is siphoned from the tree hole, it is examined for larvae in our “field lab”. The liquid in this tree hole was very dark, viscous, and full of tannins. There is no way to see anything in that slurry! We carefully sieved it to separate any larvae from the liquid, then suspended in clear, filtered water to see what we found.

Samples with mosquito larvae were labeled and bagged for later examination.

Dr. Larry Reeves, Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory, has conducted entomological research in the Sky Islands for many years and showed us some promising locations where he has previously found Tox in tree holes.

Rusty:

Our trip was not without adventure. In the monsoon season in Arizona, roads can wash out in flash floods or get covered by moving water very quickly. We had to stop several times to ensure that the dirt road was passable, and at one point, had to turn around because of flash flooding.

While we can’t be sure we found Toxorhynchites moctezuma during the expedition, samples were shipped back to the lab in Houston and will be monitored to see if eggs or early instar larvae mature into identifiable specimens. However, we did find several other species of mosquito larvae, both in tree holes and in rock pools.

One of the sycamore tree hole larvae turned into this tiny, but pretty golden colored mosquito called Aedes purpureipes. It is an unusual species with a highly restricted range.

You would think that after a long day in the field, the crew would be tired and ready to quit for the day, but what happens when a team of entomologists drive by a used tire store?

These might be looked at as “prefab” tree holes – an apartment complex of mosquito habitats! Our team took several water samples here to get a sense of the diversity of mosquitoes found in container habitats in Tucson.

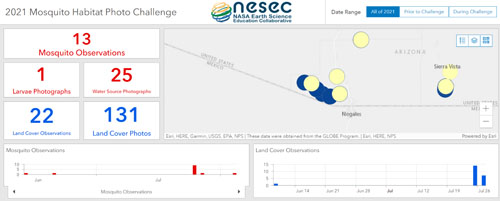

You can see our sampling transect and some of our photos here.

The GLOBE Observer Mosquito Habitat Photo Challenge is going on right now. The photos you submit during this challenge will be used to create automated classification programs that can identify mosquito larvae and the environments they prefer. Such computer programs can help prevent outbreaks of mosquito-borne disease. For more details on how you can participate, please see the Mosquito Habitat Photo Challenge webpage. And if you would like to learn more about the research being conducted with your submitted photos for the challenge, please read Rusty Low’s last blog: Machine Learning and Your Citizen Science Data.

We’d also like to know if you have found larvae in tree holes, in rock pools, or in other unusual places. Let us know where you found yours! Email rusty_low@strategies.org with your finds.

About the Authors:

Dr. Rusty Low is a senior scientist with the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies, Arlington, VA and is the Science Lead for GLOBE Observer Mosquito Habitat Mapper. Dr. Low serves as a co-PI with Dr. Carney on the NSF mosquitoAI.org project, and she also supports the NASA EPSCOR AI project teams as a senior science subject matter expert.

Anita Schiller is the founding director of the Biological Control Initiative in Harris County Precinct 4, Texas. A dedicated naturalist, her work has focused on the development of biocontrol strategies that target medically important vectors, primarily mosquitoes, for over 20 years. Ms. Schiller’s passion for responsible resource and land stewardship keeps her focused on achieving target suppression through ecological-systems-based approaches and motivated to grow the arsenal of effective biological (vector) control agents, including the mosquito assassins discussed in this blog.

Comments

View more GLOBE Observer news here.