News - GLOBE Observer

April 2024 GLOBE Eclipse Science Results

Watch the video of our GLOBE Observer Connect conversation from 13 February 2025 with blog author Ashlee Autore and GLOBE Clouds project scientist Marilé Colón Robles.

Doing Eclipse Research

On 08 April 2024, a total solar eclipse occurred over North America,

attracting millions of viewers. While some people simply enjoyed the

eclipse, others used it as a chance to contribute to scientific

research. From studying atmospheric changes to animal behaviors, many

research projects took place.

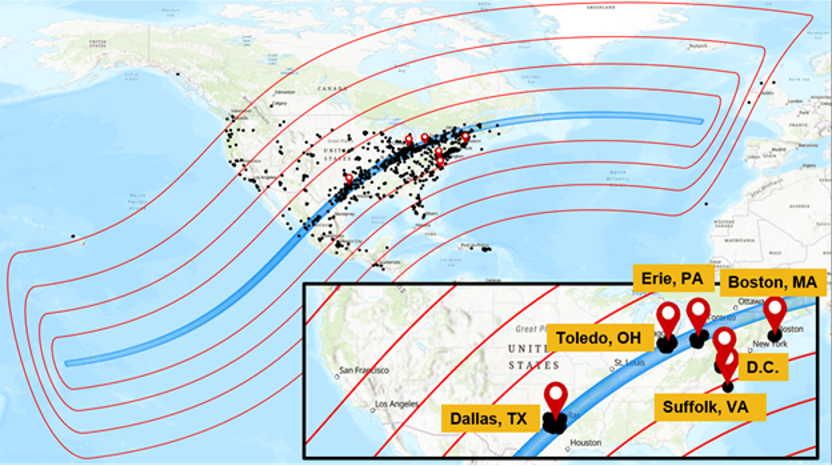

We worked on an eclipse project that used GLOBE data to look at any changes in high-level clouds, specifically cirrus clouds and contrails. Volunteers used the GLOBE Observer app to report cloud conditions every 15 - 30 minutes before, during, and after the eclipse. Volunteers also submitted air temperature data throughout the eclipse. GLOBE collected more than 7,000 cloud observations for this eclipse (see map below). Check out the Eclipse 2024 Data page on the GLOBE Observer website to see more about the data collection.

The Sun drives many processes in Earth’s atmosphere, including having impacts on air temperature, cloud formation and wind. The short-term blocking of sunlight during an eclipse can have an effect on those processes.

Why study high-level clouds during an eclipse?

Solar eclipses provide a unique opportunity to study rapid changes in the atmosphere, allowing researchers to gather data on how quickly the Earth responds to incoming solar radiation changes. For this particular study, we chose to look at high-level cloud changes during the eclipse. The relationship between high-level clouds and solar eclipses is studied less than the relationship between solar eclipses and low-level clouds. High level clouds also tend to serve as a blanket, trapping heat emitted from Earth’s surface, leading to a warming effect. This makes high-level clouds of particular interest to researchers working on understanding Earth’s environment. In contrast, low-level, thicker clouds tend to block sunlight from reaching Earth’s surface, causing cooling, on average. Of the various high-level cloud types, this research specifically focused on cirrus clouds and contrails.

Contrails are a type of high-level cloud that form when water vapor condenses and freezes around small particles (aerosols) that exist in aircraft exhaust. Contrails can be divided into three groups: short-lived, persistent non-spreading and persistent spreading. Persistent spreading contrails look like long, broad, fuzzy white lines. This is the type most likely to affect the environment because they cover a larger area and last longer than short-lived or persistent non-spreading contrails.

What were the effects of the eclipse on high-level clouds?

Using data from GLOBE Observer, satellites, weather stations, and models, we were able to paint a picture of how the eclipse may have been affecting the high-level clouds.

The GLOBE data provided us not only cloud coverage estimates, but the type of clouds present. This allowed us to identify changes in high-level clouds in a way that satellites and weather stations would not. We identified several locations that provided the best temporal coverage, meaning observations were made before, during, and after the eclipse. After cross-checking the observations with the satellite match reports for any glaring discrepancies, we were able to identify six cities for further analysis.

In this map of North America, the blue path represents the path of totality, red lines represent 20% obscuration increments outside totality, black points represent GO data, and the red locators show the six cities chosen for further analysis. The inset map highlights these six cities, where three are within totality: Erie, PA; Toledo, OH; and Dallas, TX; and three are outside totality: Boston, MA; Washington, D.C.; and Suffolk, VA.

Overall, we found that GLOBE Observer volunteers reported similar cloud coverage as the satellites and similar trends in cloud coverage changes. The weather station reports often are not capable of accurately reporting high-level cloud coverage, but did offer valuable information on any surface weather changes.

After dividing the GLOBE data into 15-minute increments, we found the volunteers often reported an increase in cirrus clouds and contrails leading up to the local eclipse maximum. This led us to look into flight paths, to see if the number of flights were increasing, and model data, to show what may have been changing in the upper atmosphere. We didn’t find any notable increase in flights, but the models did show the potential for contrail formation increased for most locations during the study period. These models are not available for small timescale changes, such as 15 minutes, so they largely provide a bigger picture of the conditions that affect contrails.

Images submitted via GLOBE Observer. All images were taken in Toledo, OH at the same location, by the same person. From left to right, the images were taken at 17:19 UTC, 19:10 UTC, and 20:19 UTC. Totality at this location was between approximately 19:12 and 19:14 UTC. These images show how some clouds changed throughout the eclipse, including contrails.

One important factor in contrail formation and growth is relative humidity with respect to ice (RHI), which is not the same as relative humidity we use at the surface. An RHI greater than or equal to 80% tells us there is potential for contrails to form; the higher the RHI, the greater the potential and the more likely it is for contrails to persist, spread, and even grow into cirrus clouds.

We used models provided by the Goddard Space Flight Center to look at how RHI may have changed during the eclipse. These models don’t capture or accurately account for the small changes in RHI that may occur due to an eclipse, which means we can’t use them to prove the eclipse made atmospheric conditions more favorable for cirrus clouds and contrails to form. However, Tthe models do allow us to see that conditions did grow more favorable overall during the eclipse period. In particular, these RHI models showed RHI increased in each location as the eclipse maximum approached, with each location maintaining an RHI greater than 80%.

We also used models provided by the NASA Langley SatCORPS team. These models are ensembles, meaning they were derived from several other models. They used air temperature, pressure, relative humidity, and wind shear to identify regions of the U.S. that had potential for contrail formation. We used this information to help us identify what changes may have been occurring in the atmosphere. None of the models we considered were capable of showing us small-scale changes, such as within 15 minutes, but they still provided valuable information. The models were able to confirm that atmospheric conditions did become more favorable for contrail formation during the eclipse. Given the scale of the models, we cannot definitively say the solar eclipse caused atmospheric conditions to become more favorable for contrails to form. The models do, however, provide supporting evidence that the observers did indeed notice an increase in contrails.

Contributions of Citizen Science

All of Earth’s processes are affected by the Sun in some way. By continuing to study how changes in solar radiation affect these high-level clouds, researchers may be able to more accurately and confidently predict where and when contrails form. This could result in changes to air travel, such as times of flights, conditions planes will fly in, or engine and fuel types of planes, to help control the effect humans have.

The data collected through GLOBE made this research possible, given the current limitations of satellites and weather stations. The GLOBE data were able to give us a picture of what was happening throughout the eclipse in ways we wouldn’t have otherwise been able to see. Having citizen science observations helps advance scientific research by providing us with a bottom-up view of the Earth and showing us what can change in the atmosphere during short time scale events not covered by models or other observation types. Thank you to everyone who has, and continues to, collect data!

Update 26 March 2025: This research has now been published in the Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society.

Autore, A. M., Dodson, J. B., Duda, D. P., Robles, M. C., Weaver, K. L., Taylor, J. E., Rogerson, T. M., & Kohl, H. (2025). GLOBE Eclipse 2024: A Case Study of the Effects of the April 2024 Total Solar Eclipse on Cirrus Clouds and Contrails in the United States of America. Bulletin of the AAS, 56(9). https://doi.org/10.3847/25c2cfeb.d9ddc39b

About the Author:

Ashlee Autore is a data scientist for NASA GLOBE Clouds and a developer for My NASA Data, both based out of the Science Directorate at NASA Langley Research Center with ADNET Systems, Inc. Ashlee analyzes data collected through GLOBE and includes the results in research projects. She also maintains the My NASA Data website and acts as a subject matter expert for some of the materials on the website.

Comments

View more GLOBE Observer news here.