News - GLOBE Observer

Where does the land become water?

Communities have long-since been focused on where water is located, and it’s an important science question that relates to all of us here on Earth. Through the “Where is the Water” challenge, we are asking you to use the Land Cover tool in The GLOBE Program’s GLOBE Observer app to photograph where you see water “edges.” The edge of water is an area that shifts in time and space, causing problems for scientists who attempt to map, measure, and monitor this vital resource from space. For example, if the Sun isn’t high enough in the sky when the satellite passes over the area, trees or other tall objects will cast a shadow, and scientists won’t see the location where land turns into water. On-ground GLOBE Observer Land Cover observations can provide a reference point via photographs for these edge locations.

Your ground observations of water can help support the analysis of satellite data in many scenarios. For example, a water feature might be smaller than what can be seen by the resolution of a satellite. This causes many water features to not be recorded at all. Other small water features, like a narrow river, may only be detected by their shape winding on the landscape, giving a clue that water is present.

Secondly, some areas are actually a mix of water and vegetation, like shorelines, where an area may be both green from plants and dark from sunlight going into the surface water. A common error in land cover maps is mistaking a wetland for a forest because the water body absorbs sunlight just like a tall tree canopy does. This is where geo-referenced ground photos submitted through the GLOBE Observer mobile app can inform where that edge of water and land is actually located.

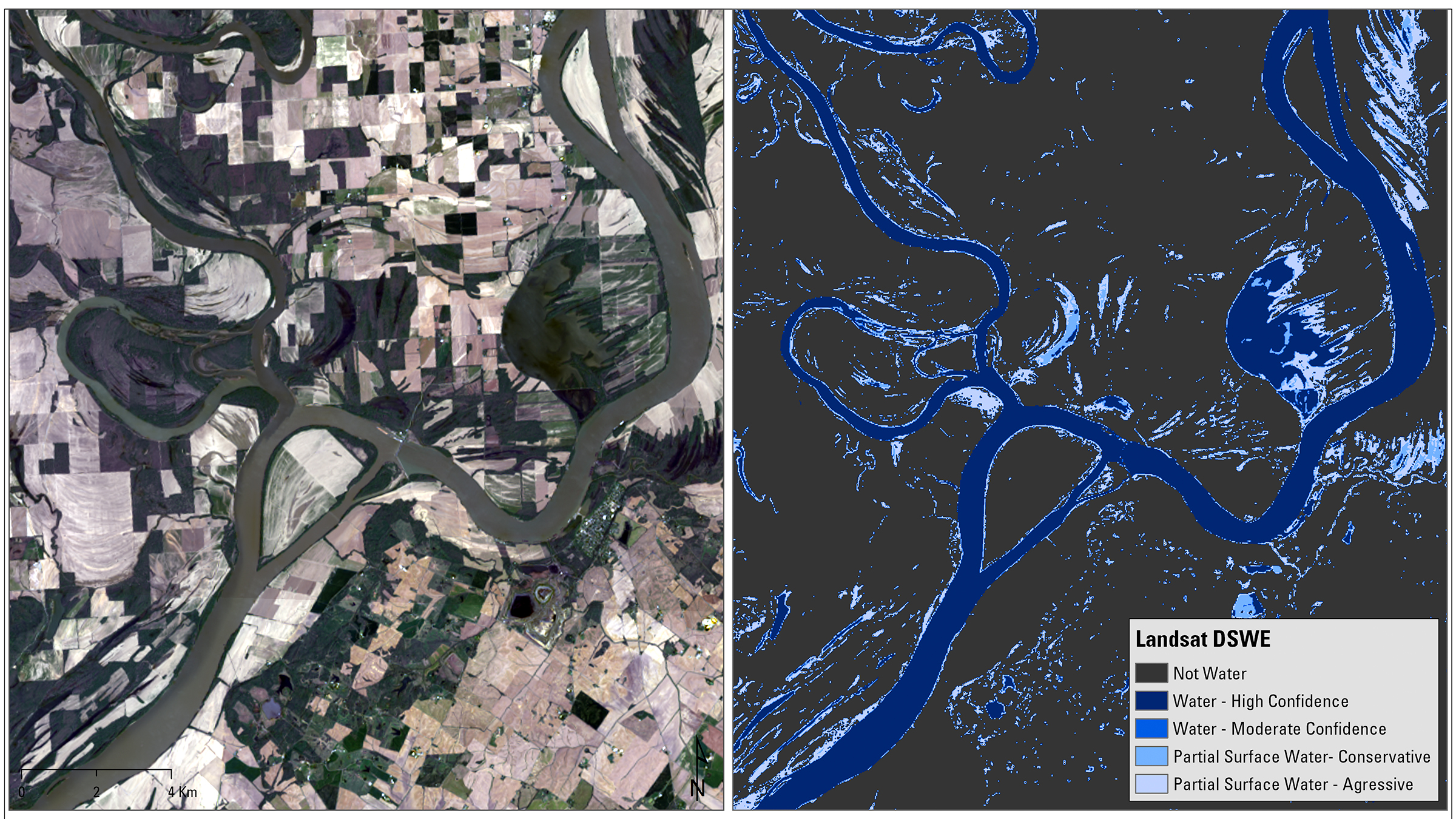

The Landsat Dynamic Surface Water Extent science product was

developed to map Earth’s constantly changing surface water over time.

As shown in this sample, the center of the river is easy to identify

as water, but the edges are less certain.

Image courtesy Michelle A . Bouchard, based on Landsat data from

the USGS.

So why do “edges” matter? Water is always changing. Just looking at a map, you can see places that are always water, places that are sometimes water, and places that are never water. Some lakes, for example, are sometimes there and then sometimes not. This ephemeral nature is an important characteristic, but we don’t know the exact timing. Depending on the season, certain places may be flooded. (Please be safe and don’t put yourself in danger for an observation!) Or you may see evidence or erosion or past floods in places where water is not. Water changes the land, especially in the boundary where two surface conditions meet.

Water edges can also change rapidly in response to seasonal changes in precipitation, temperature, or extreme Earth events such as flooding. Other changes take place over longer periods of time. You may also see water edges or locations shift in response to deliberate changes in land cover which are the result of land-use practices. Human modifications to the landscape surround many of us, but you could be unaware because the area is covered by trees, shrubs, grasses, or water.

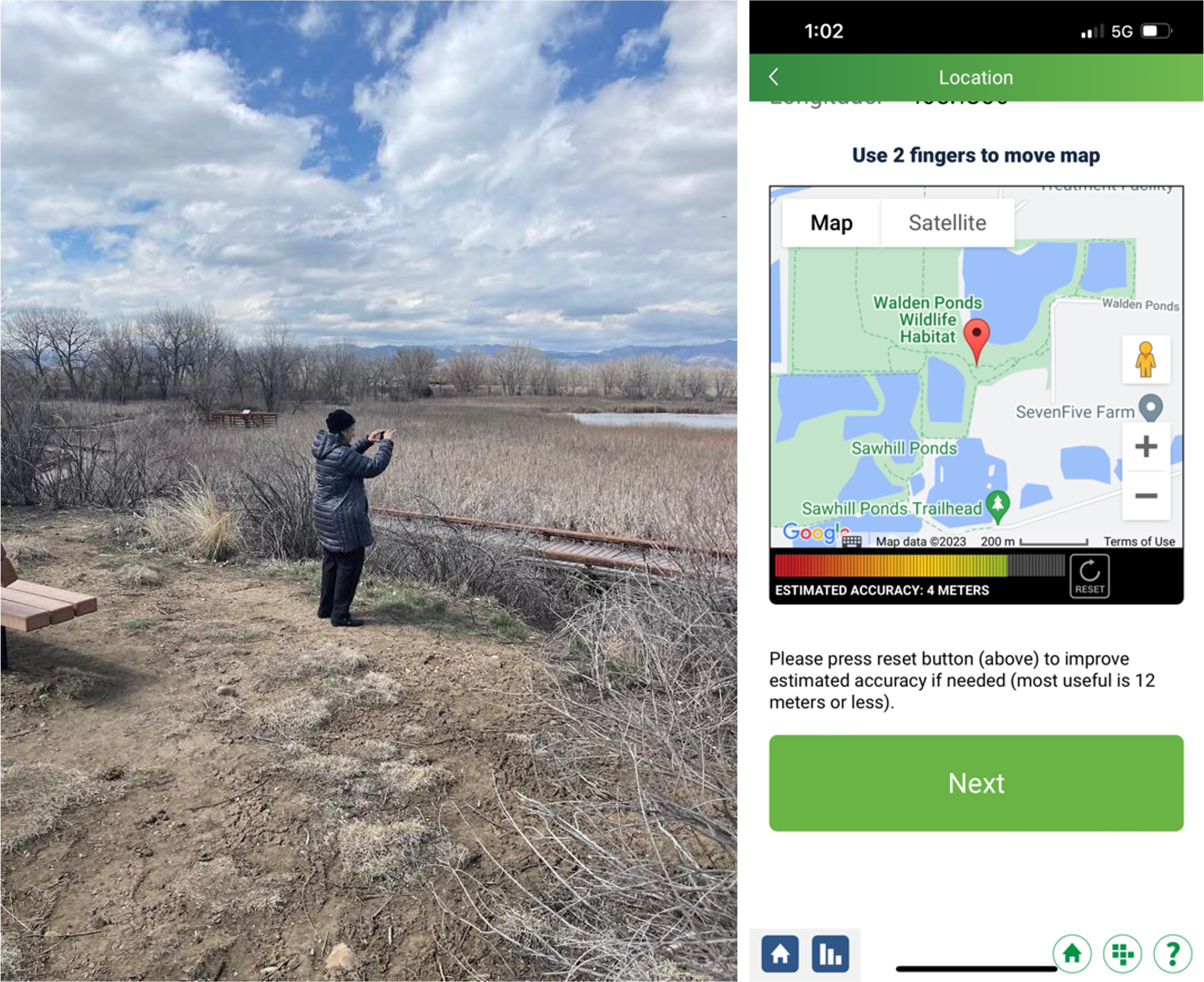

Water edges are also important from a health perspective, because of seasonal mosquito breeding habitats. Flooded vegetation is frequently found at water edges, and this is a place where water tends to be still. Mosquito larvae need still water so that they can control their movement and forage for food. The vegetation also provides protection from predators. Dr. Russanne (Rusty) Low (Science Lead for the Mosquito Habitat Mapper tool within the GLOBE Observer app) has noted that a place where she often walks her dog, Walden Ponds, is such a place.

“My goal on today’s walk was to observe surface water the way volunteers will during GLOBE Observer’s “Where is the Water?” Challenge in May 2023. It’s too early for me to contribute mosquito data in my areas, but I know from previous visits that this area supports many mosquitoes, which in turn support not only macroinvertebrates and small amphibians but also the waterfowl that inhabit this area. Wetlands are fondly referred to by conservationists as ‘nature’s food court,’ for the biodiversity that inhabits these biomes. Along the shoreline, the mix of water, grasses, shrubs, and trees provide a productive and protective habitat to many organisms and is a favored place for bird watching year-round.”

Dr. Low used the Land Cover tool in GLOBE Observer to document

surface water in Walden Ponds, Boulder, Colorado.

The GLOBE Observer land cover photos documenting the wetland

around Walden Ponds in spring 2023.

She continues:

“It’s April in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, USA, and we still have winter weather conditions. The nearby mountains are covered by snow and ice, but the flood of spring meltwater is coming soon to recharge our creeks and streams. Wetlands are natural sponges, absorbing snowmelt and precipitation run-off, while recharging groundwater and slowly releasing water downstream, protecting settlements from seasonal flooding. This is an important ecosystem service of wetlands.”

While walking, Rusty observed:

“There is less standing water than you see in the spring and early summer, but there is standing water underneath the marsh vegetation. The down photos provide a close-up view and shows that there are dark spaces between the cattails, reeds, and grass, which is standing water.”

The black spots in the down photo from Dr. Low's land cover

observation hint at water beneath the vegetation.

The area that Rusty is walking in has some history too. Prior to 1958, the area was a rich floodplain grassland and supported livestock grazing. It was purchased in 1958 by the city of Boulder (CO, USA) to mine gravel for road construction. The mining left deep barren land cover holes in the ground that eventually filled with groundwater and precipitation and transitioned to a new land cover type (water) and thus becoming a different area for wildlife.

Then and now: Photos from City of Boulder Parks

Rusty adds:

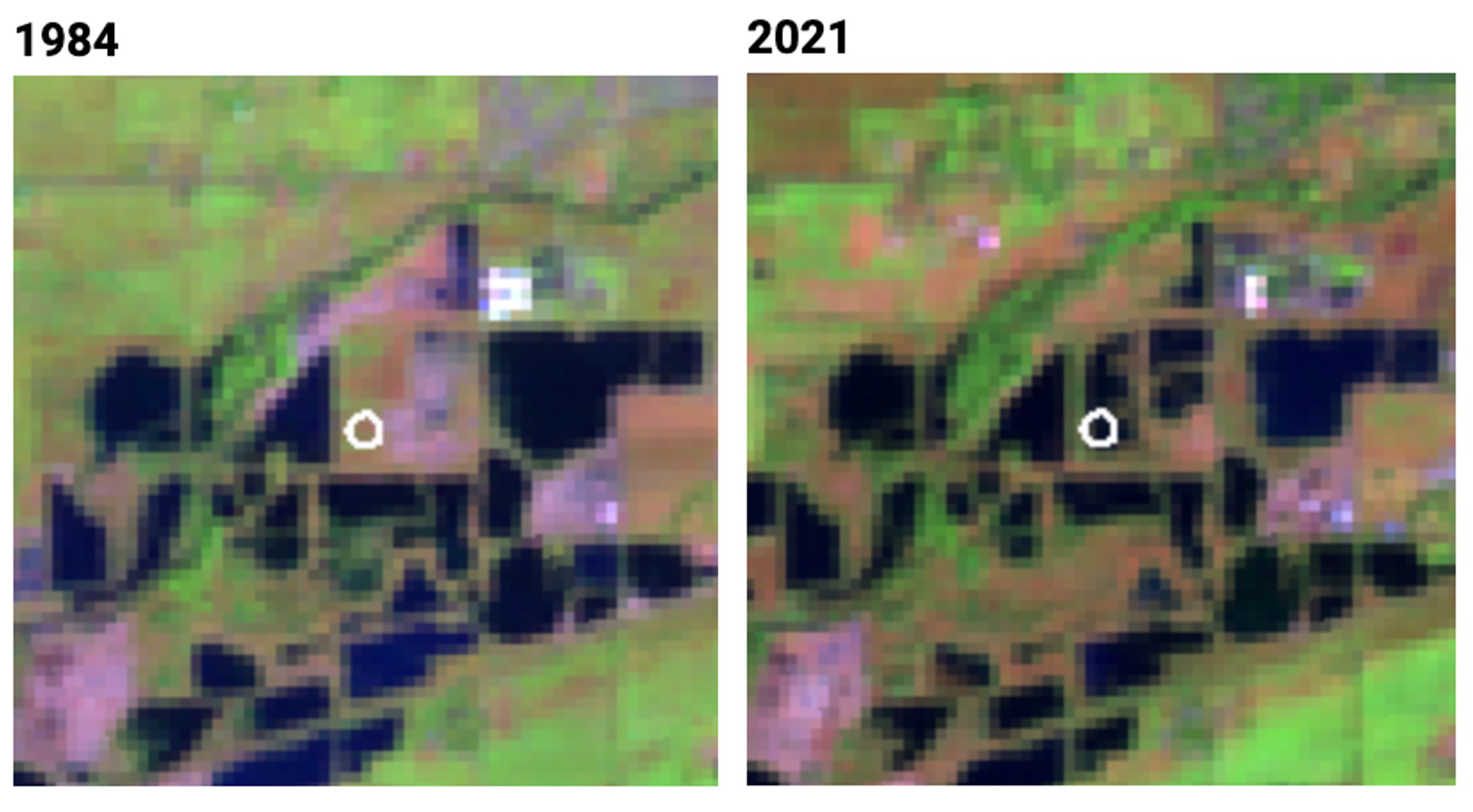

“I was interested in this history and wondered if satellite images could detect the water at this site. We tend to associate mosquito habitat with water and vegetation. With the guidance from Peder, I used the Landsat Time Series Explorer web app (developed by Justin Braaten) to search and display what was available in the Landsat archive available in Google Earth Engine. I was able to focus just on this small area with a series of 2 kilometer-wide image chip for each year between 1984 to 2021. When I compared all the images across the years, it was easy to see different colors before and after the pivotal year of 1997. This imagery confirmed what I saw happen on the ground during that time as the current configuration of surface water (ponds) begin to appear. I wondered whether this area was a mosquito habitat back when it was a barren area?”

Landsat satellite images from 1984, left, and 2021, show

significant change around Walden Ponds, Boulder, Colorado, as the

bare ground (pink) filled in with water (black) and vegetation (green).

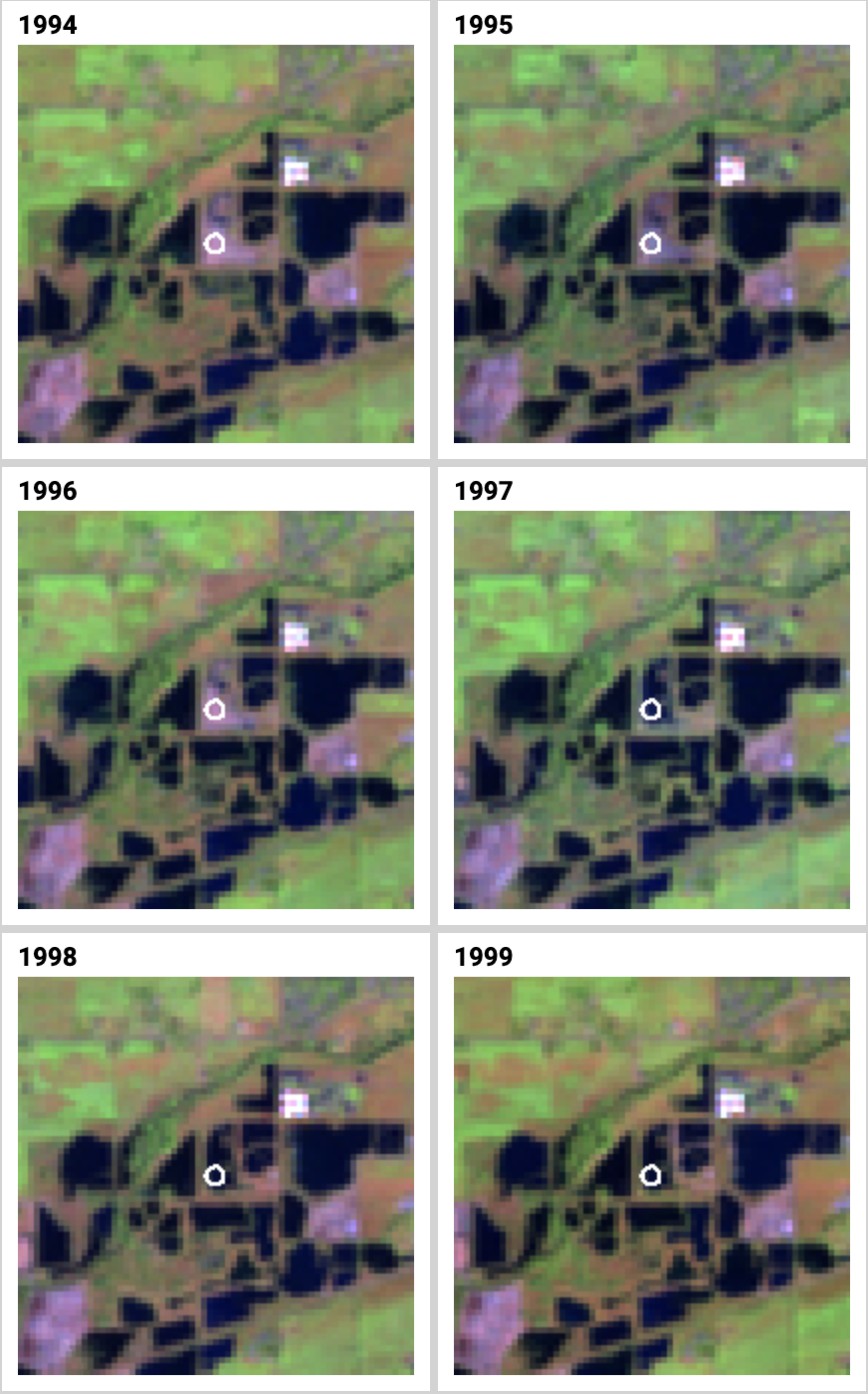

Yearly Landsat satellite images show that the area Dr. Low

observer (white circle) transitioned to water in 1996 and 1997.

“Peder also shared this Landsat animation tool that gave me a different way to see these individual satellite images.”

The changes detected in the Landsat image series stand out more in

an animated series of annual images.

This example from Rusty about Walden Ponds shows how water distribution on the Earth’s surface can change dramatically in a short period of time. The land cover shift from bare to water is the result of changing land use in a particular area; however seasonal changes in precipitation and extreme Earth events are other factors that influence where and when we see surface water.

We invite you to help us answer the question of ‘Where is the Water?’ in the month of May, 2023. To join the challenge, download the GLOBE Observer app, get trained, and contribute your observations of water and mosquito habitats to this science and education database! Where is the Water? A GLOBE Observer Data Challenge runs 01 May to 31 May 2023. To learn more visit the challenge website.

Comments

View more GLOBE Observer news here.